UT researchers develop (r)evolutionary circuits

Researchers of the MESA+ Institute for Nanotechnology and the CTIT Institute for ICT Research at the University of Twente in The Netherlands have demonstrated working electronic circuits that have been produced in a radically new way, using methods that resemble Darwinian evolution. The size of these circuits is comparable to the size of their conventional counterparts, but they are much closer to natural networks like the human brain. The findings promise a new generation of powerful, energy-efficient electronics, and have been published in the leading British journal Nature Nanotechnology.

One of the greatest successes of the 20th century has been the development of digital computers. During the last decades these computers have become more and more powerful by integrating ever smaller components on silicon chips. However, it is becoming increasingly hard and extremely expensive to continue this miniaturisation. Current transistors consist of only a handful of atoms. It is a major challenge to produce chips in which the millions of transistors have the same characteristics, and thus to make the chips operate properly. Another drawback is that their energy consumption is reaching unacceptable levels. It is obvious that one has to look for alternative directions, and it is interesting to see what we can learn from nature. Natural evolution has led to powerful ‘computers’ like the human brain, which can solve complex problems in an energy-efficient way. Nature exploits complex networks that can execute many tasks in parallel.

Moving away from designed circuits

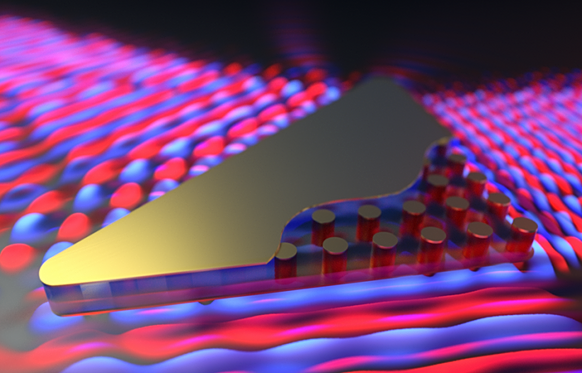

The approach of the researchers at the University of Twente is based on methods that resemble those found in Nature. They have used networks of gold nanoparticles for the execution of essential computational tasks. Contrary to conventional electronics, they have moved away from designed circuits. By using 'designless' systems, costly design mistakes are avoided. The computational power of their networks is enabled by applying artificial evolution. This evolution takes less than an hour, rather than millions of years. By applying electrical signals, one and the same network can be configured into 16 different logical gates. The evolutionary approach works around - or can even take advantage of - possible material defects that can be fatal in conventional electronics.

Powerful and energy-efficient

It is the first time that scientists have succeeded in this way in realizing robust electronics with dimensions that can compete with commercial technology. According to prof. Wilfred van der Wiel, the realized circuits currently still have limited computing power. “But with this research we have delivered proof of principle: demonstrated that our approach works in practice. By scaling up the system, real added value will be produced in the future. Take for example the efforts to recognize patterns, such as with face recognition. This is very difficult for a regular computer, while humans and possibly also our circuits can do this much better." Another important advantage may be that this type of circuitry uses much less energy, both in the production, and during use. The researchers anticipate a wide range of applications, for example in portable electronics and in the medical world.