Researchers in the Light-Matter Interactions Unit led by Professor Síle Nic Chormaic at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) have developed an on-off switch with ultrathin optical fibers, which could be used for data transfer in the future. This research was published in the New Journal of Physics.

0101000001101000011110010111001101101001011000110111001100100000011010010111001100100000011001100111010101101110 means “Physics is fun” in binary code. Computers translate every letter, number, sign, space, image and sound to a set of 8 ones and zeros. For example, 01010000 corresponds to the letter P. While you type, your computer transfers your words to another distant computer by sending a series of ones and zeros encoded in light through standard optical fibers. Switching the light beam on and off very quickly generates the ones and zeros. These bits of information are converted to electronic signals at a node, usually a router or server, and finally appear as text on the screen of your recipient. While this is the classical way of transferring information online, OIST researchers are exploring more efficient ways of transferring data, using the quantum properties of light and matter. They have managed to create an on/off switch based on the quantum characteristics of rubidium atoms in the presence of light of different wavelengths. This proof-of-concept system could be used as a building block in a quantum network, the future of our internet.

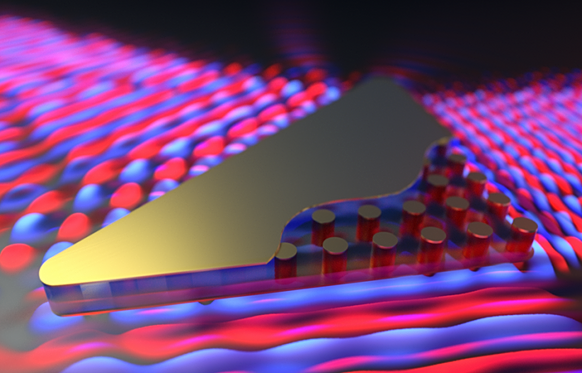

The OIST team’s experimental setup consists of two lasers that produce light at different wavelengths, an optical nanofiber used to guide light, and rubidium atoms trapped around it. The peculiarity of optical nanofibers is their super-thin diameter. For this study the diameter was 350 nanometers, about 300 times thinner than the thickness of a sheet of paper. The diameter is even smaller than the wavelength of the light guided by the fiber. Some of the light, therefore, leaks outside the nanofiber and interacts with the rubidium atoms that are trapped around it. These atoms can function as a quantum node, a redistribution point of a network, the equivalent of today’s servers.

The off switch condition is obtained when only the laser producing 780 nm is on. In this case, at the point where light leaks outside of the optical nanofiber, the rubidium atoms absorb the maximum amount of light and almost no light can continue to pass along the fiber. In contrast, the switch is turned on when both 776 nm and 780 nm lights are present. In this situation, most of the light is transmitted through the optical nanofiber and the rubidium atoms absorb it only minimally.

Since the optical nanofiber is directly connected to a standard optical fiber, the light can, in principle, be transferred to another quantum system or node some distance away, in the same way you can send a message from your computer to that of your friend’s in another location.

“Using optical nanofibers would allow us to fully integrate our system with existing fiber-based communication networks. While the current work is far from being a practical solution to quantum information, it brings the notion of using atoms and light to develop real devices based on quantum mechanics ever closer to fulfilment”, explains Professor Síle Nic Chormaic.

While the experiment at OIST currently only generates zeros/off and ones/on consecutively, further exploitation of the quantum behavior of atoms should allow the research team to send light as a combination of “on” and “off” at the same time. In this way, in the future, quantum networks will be able to process more data simultaneously, increase efficiency of information transfer and also provide better cyber security.

“It has been very exciting to work with optical nanofibers which can guide light extremely efficiently even if their diameter is much smaller than the wavelength of light itself. These systems are sure to give us significant progress in quantum networks in the years to come,” enthuses Ravi Kumar, one of the authors of this study and a PhD student at University College Cork in Ireland, doing his research work at OIST.