|

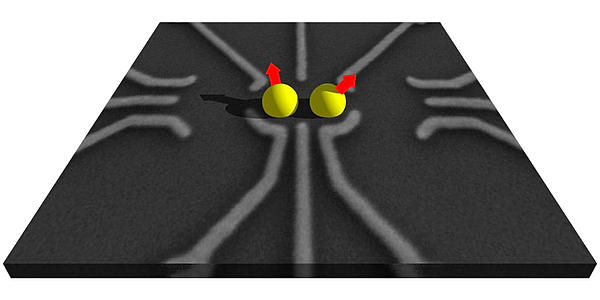

Researchers coupled a diamond nanoparticle with a magnetic vortex to control electron spin in nitrogen-vacancy defects. @ Case Western Reserve University

|

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University have developed a way to swiftly and precisely control electron spins at room temperature.

The technology, described in Nature Communications, offers a possible alternative strategy for building quantum computers that are far faster and more powerful than today's supercomputers.

"What makes electronic devices possible is controlling the movement of electrons from place to place using electric fields that are strong, fast and local," said physics Professor Jesse Berezovsky, leader of the research. "That's hard with magnetic fields, but they're what you need to control spin."

Other researchers have searched for materials where electric fields can mimic the effects of a magnetic field, but finding materials where this effect is strong enough and still works at room temperature has proven difficult.

"Our solution," Berezovsky said, "is to use a magnetic vortex."

Berezovsky worked with physics PhD students Michael S. Wolf and Robert Badea.

The researchers fabricated magnetic micro-disks that have no north and south poles like those on a bar magnet, but magnetize into a vortex. A magnetic field emanates from the vortex core. At the center point, the field is particularly strong and rises perpendicular to the disk.

The vortices are coupled with diamond nanoparticles. In the diamond lattice inside each nanoparticle, several individual spins are trapped inside of defects called nitrogen vacancies.

The scientists use a pulse from a laser to initialize the spin. By applying microwaves and a weak magnetic field, Berezovsky's team can move the vortex in nanoseconds, shifting the central point, which can cause an electron to change its spin.

In what's called a quantum coherent state, the spin can act as a quantum bit, or qubit--the basic unit of information in a quantum computer.

In current computers, bits of information exist in one of two states: zero or one. But in a superposition state, the spin can be up and down at the same time, that is, zero and one simultaneously. That capability would allow for more complex and faster computing.

"The spins are close to each other; you want spins to interact with their neighbors in quantum computing," Berezovsky said. "The power comes from entanglement."

The magnetic field gradient produced by a vortex proved sufficient to manipulate spins just nanometers apart.

In addition to computing, electrons controlled in coherent quantum states might be useful for extremely high-resolution sensors, the researchers say. For example, in an MRI, they could be used to sense magnetic fields in far more detail than with today's technology, perhaps distinguishing atoms.

Controlling the electron spins without destroying the coherent quantum states has proven difficult with other techniques, but a series of experiments by the group has shown the quantum states remain solid. In fact, "the vortex appears to enhance the microwave field we apply," Berezovsky said.

The scientists are continuing to shorten the time it takes to change the spin, which is a key to high-speed computing. They are also investigating the interactions between the vortex, microwave magnetic field and electron spin, and how they evolve together.

Case Western Reserve University

More stories on Nanotechnology World Association