The mission of the NWA is to globally promote nanotechnology solutions adoption across industries by connecting entrepreneurs with researchers, start-ups with investors, providers with potential customers, employers with job seekers, key players with one another, in an independent and mainly industry-oriented advocacy group – inclusive of business, academia, business-supporting associates, as well as affiliate government agencies and other associations.

Showing posts with label microscopy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label microscopy. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 21, 2016

New electron microscope method detects atomic-scale magnetism

Scientists can now detect magnetic behavior at the atomic level with a new electron microscopy technique developed by a team from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Uppsala University, Sweden. The researchers took a counterintuitive approach by taking advantage of optical distortions that they typically try to eliminate.

“It’s a new approach to measure magnetism at the atomic scale,” ORNL’s Juan Carlos Idrobo said.

“We will be able to study materials in a new way. Hard drives, for instance, are made by magnetic domains, and those magnetic domains are about 10 nanometers apart.” One nanometer is a billionth of a meter, and the researchers plan to refine their technique to collect magnetic signals from individual atoms that are ten times smaller than a nanometer.

“If we can understand the interaction of those domains with atomic resolution, perhaps in the future we will able to decrease the size of magnetic hard drives,” Idrobo said. “We won’t know without looking at it.”

Researchers have traditionally used scanning transmission electron microscopes to determine where atoms are located within materials. This new technique allows scientists to collect more information about how the atoms behave.

“Magnetism has its origins at the atomic scale, but the techniques that we use to measure it usually have spatial resolutions that are way larger than one atom,” Idrobo said. “With an electron microscope, you can make the electron probe as small as possible and if you know how to control the probe, you can pick up a magnetic signature.”

The ORNL-Uppsala team developed the technique by rethinking a cornerstone of electron microscopy known as aberration correction. Researchers have spent decades working to eliminate different kinds of aberrations, which are distortions that arise in the electron-optical lens and blur the resulting images.

Instead of fully eliminating the aberrations in the electron microscope, the researchers purposely added a type of aberration, called four-fold astigmatism, to collect atomic level magnetic signals from a lanthanum manganese arsenic oxide material. The experimental study validates the team’s theoretical predictions presented in a 2014 Physical Review Lettersstudy.

“This is the first time someone has used aberrations to detect magnetic order in materials in electron microscopy,” Idrobo said. “Aberration correction allows you to make the electron probe small enough to do the measurement, but at the same time we needed to put in a specific aberration, which is opposite of what people usually do.”

Idrobo adds that new electron microscopy techniques can complement existing methods, such as x-ray spectroscopy and neutron scattering, that are the gold standard in studying magnetism but are limited in their spatial resolution.

The study is published as “Detecting magnetic ordering with atomic size electron probes,” in the journal of Advanced Structural and Chemical Imaging. Coauthors are ORNL’s Juan Carlos Idrobo, Michael McGuire, Christopher Symons, Ranga Raju Vatsavai, Claudia Cantoni and Andrew Lupini; and Uppsala University’s Ján Rusz and Jakob Spiegelberg.

The electron microscopy experiments were conducted at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, a DOE Office of Science User Facility at ORNL. The research was supported by DOE’s Office of Science.

ORNL is managed by UT-Battelle for the Department of Energy's Office of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. DOE’s Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Nanotechnology World Association

Monday, November 9, 2015

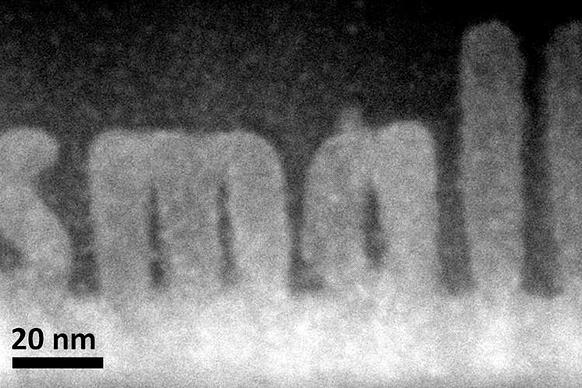

New electron microscopy method sculpts 3-D structures at atomic level

Electron microscopy researchers at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory have developed a unique way to build 3-D structures with finely controlled shapes as small as one to two billionths of a meter.

The ORNL study published in the journal Small demonstrates how scanning transmission electron microscopes, normally used as imaging tools, are also capable of precision sculpting of nanometer-sized 3-D features in complex oxide materials.

By offering single atomic plane precision, the technique could find uses in fabricating structures for functional nanoscale devices such as microchips. The structures grow epitaxially, or in perfect crystalline alignment, which ensures that the same electrical and mechanical properties extend throughout the whole material.

“We can make smaller things with more precise shapes,” said ORNL’s Albina Borisevich, who led the study. “The process is also epitaxial, which gives us much more pronounced control over properties than we could accomplish with other approaches.”

ORNL scientists happened upon the method as they were imaging an imperfectly prepared strontium titanate thin film. The sample, consisting of a crystalline substrate covered by an amorphous layer of the same material, transformed as the electron beam passed through it. A team from ORNL’s Institute for Functional Imaging of Materials, which unites scientists from different disciplines, worked together to understand and exploit the discovery.

“When we exposed the amorphous layer to an electron beam, we seemed to nudge it toward adopting its preferred crystalline state,” Borisevich said. “It does that exactly where the electron beam is.”

The use of a scanning transmission electron microscope, which passes an electron beam through a bulk material, sets the approach apart from lithography techniques that only pattern or manipulate a material’s surface.

“We’re using fine control of the beam to build something inside the solid itself,” said ORNL’s Stephen Jesse. “We’re making transformations that are buried deep within the structure. It would be like tunneling inside a mountain to build a house.”

The technique offers a shortcut to researchers interested in studying how materials’ characteristics change with thickness. Instead of imaging multiple samples of varying widths, scientists could use the microscopy method to add layers to the sample and simultaneously observe what happens.

“The whole premise of nanoscience is that sometimes when you shrink a material it exhibits properties that are very different than the bulk material,” Borisevich said. “Here we can control that. If we know there is a certain dependence on size, we can determine exactly where we want to be on that curve and go there.”

Theoretical calculations on ORNL’s Titan supercomputer helped the researchers understand the process’s underlying mechanisms. The simulations showed that the observed behavior, known as a knock-on process, is consistent with the electron beam transferring energy to individual atoms in the material rather than heating an area of the material.

“With the electron beam, we are injecting energy into the system and nudging where it would otherwise go by itself, given enough time,” Borisevich said. “Thermodynamically it wants to be crystalline, but this process takes a long time at room temperature.”

The study is published as “Atomic-level sculpting of crystalline oxides: towards bulk nanofabrication with single atomic plane precision.”

Coauthors are ORNL’s Stephen Jesse, Qian He, Andrew Lupini, Donovan Leonard, Raymond Unocic, Alexander Tselev, Miguel Fuentes-Cabrera, Bobby Sumpter, Sergei Kalinin and Albina Borisevich, Vanderbilt University’s Mark Oxley and Oleg Ovchinnikov and the National University of Singapore’s Stephen Pennycook.

The research was conducted as part of ORNL’s Institute for Functional Imaging of Materials and was supported by DOE’s Office of Science and ORNL’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program. The study used resources at ORNL’s Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences and the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which are both DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

ORNL is managed by UT-Battelle for the Department of Energy's Office of Science. DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Monday, June 1, 2015

Novel X-ray lens sharpens view into the nano world

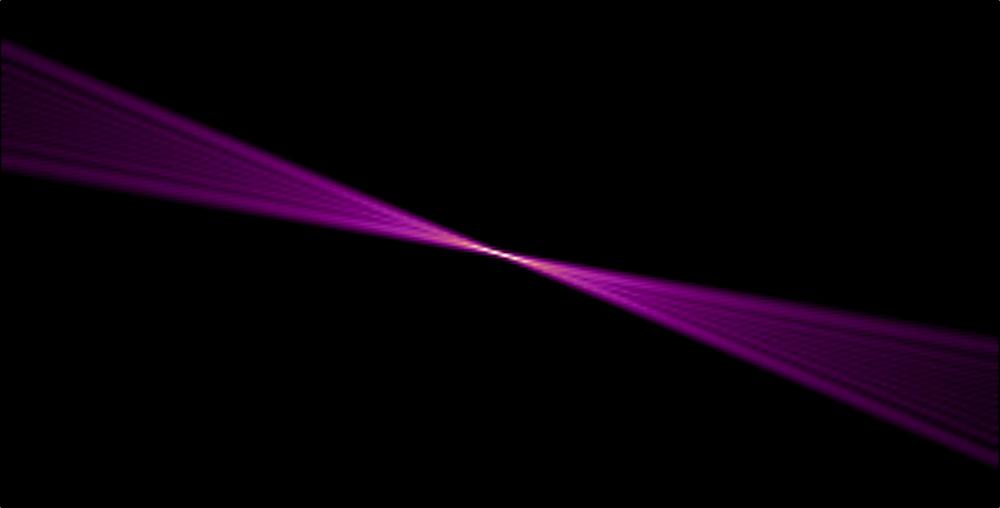

|

| Reconstruction of the focused X-ray wave. The lens achieves the spot size of 8 nanometres at the smallest waist. Credit: Saša Bajt/DESY |

DESY team produces innovative high-power X-ray lens

A team led by DESY scientists has designed, fabricated and successfully tested a novel X-ray lens that produces sharper and brighter images of the nano world. The lens employs an innovative concept to redirect X-rays over a wide range of angles, making a high convergence power. The larger the convergence the smaller the details a microscope can resolve, but as is well known it is difficult to bend X-rays by large enough angles. By fabricating a nano-structure that acts like an artificial crystal it was possible to mimic a high refracting power. Although the fabrication needed to be controlled at the atomic level — which is comparable to the wavelength of X-rays — the DESY scientists achieved this precision over an unprecedented area, making for a large working-distance lens and bright images. Together with the improved resolution these are key ingredients to make a super X-ray microscope. The team led by Dr. Saša Bajt from DESY presents the novel lens in the journal Scientific Reports (Nature Publishing Group).

An alternative means to bend X-rays is to use crystals. A crystal lattice diffracts X-rays, as the German physicist Max von Laue discovered a century ago. Today, artificial crystals can be tailor-made to sharply focus X-rays by depositing different materials layer by layer. From this building block comes the multilayer Laue lens or MLL, made by coating a substrate with thin layers of the chosen substances. “However, conventional Laue lenses are limited in their converging power for geometric reasons,” explains Bajt. “To gain the maximum power, the layers of a MLL need to be slightly tilted against each other.” As theoretical calculations have shown, all layers of such a “wedged” MLL must lie perpendicular on a circle with a radius of twice the focal length.

This rather specific condition could not be fabricated — until now. Bajt’s team invented a new production process, where a mask partially shields the substrate from the depositing material. In the half-shade of the mask a wedged structure builds up, and the tilt of the layers is controlled simply by adjusting the spacing of the mask to the substrate. The wedged MLL is then cut from the penumbra region. "Before us, no one came close to building such a wedged lens", says Bajt.

The researchers manufactured a wedged lens from 5500 alternating layers of silicon carbide (SiC) and tungsten (W), varying in thickness. The final lens cut from these deposits was 40 micrometres (millionths of a metre) wide, 17.5 micrometres thick and 6.5 micrometres deep.

The team tested their novel lens at DESY's ultra brilliant X-ray source PETRA III. The test at the experimental station P11 showed that the lens produced a focus just 8 nm wide, which is close to the design value of 6 nm. The tests also showed that the intensity profile across the lens is very uniform, a prerequisite for high quality images. The lens design allows to transmit up to 60 per cent of the incoming X-rays to the sample.

The scientists focussed the X-ray beam in just one direction, resulting in a thin line. Focussing in two dimensions to obtain a small spot can be done by simply using two lenses in line, one focusing horizontally and the other vertically. “Our results prove out our fabrication technique to achieve lenses of high focussing power. We believe we have the requisite control to achieve even higher power lenses,” elaborates Bajt. “It appears that the long-sought goal of focusing X-rays to a nanometre is in reach.” This will put X-ray imaging on par with the quality achieved with scanning electron microscopes, that typically have a resolution of 4 nm. The advantage is that X-ray imaging is not limited to viewing surfaces or extremely thin samples only, but can penetrate a sample. “Our novel lens concept will help scientists to peer deeper into the nanocosm and make previously inaccessible details visible,” says Bajt.

The scientists focussed the X-ray beam in just one direction, resulting in a thin line. Focussing in two dimensions to obtain a small spot can be done by simply using two lenses in line, one focusing horizontally and the other vertically. “Our results prove out our fabrication technique to achieve lenses of high focussing power. We believe we have the requisite control to achieve even higher power lenses,” elaborates Bajt. “It appears that the long-sought goal of focusing X-rays to a nanometre is in reach.” This will put X-ray imaging on par with the quality achieved with scanning electron microscopes, that typically have a resolution of 4 nm. The advantage is that X-ray imaging is not limited to viewing surfaces or extremely thin samples only, but can penetrate a sample. “Our novel lens concept will help scientists to peer deeper into the nanocosm and make previously inaccessible details visible,” says Bajt.

Source: http://www.desy.de/news/news_search/index_eng.html?openDirectAnchor=801

Wednesday, October 2, 2013

Seeing through silicon

New microscopy technique allows scientists to visualize cells through the walls of silicon microfluidic devices.

Scientists at MIT and the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) have developed a new type of microscopy that can image cells through a silicon wafer, allowing them to precisely measure the size and mechanical behavior of cells behind the wafer.

The new technology, which relies on near-infrared light, could help scientists learn more about diseased or infected cells as they flow through silicon microfluidic devices.

“This has the potential to merge research in cellular visualization with all the exciting things you can do on a silicon wafer,” says Ishan Barman, a former postdoc in MIT’s Laser Biomedical Research Center (LBRC) and one of the lead authors of a paper describing the technology in the Oct. 2 issue of the journal Scientific Reports.

Other lead authors of the paper are former MIT postdoc Narahara Chari Dingari and UTA graduate students Bipin Joshi and Nelson Cardenas. The senior author is Samarendra Mohanty, an assistant professor of physics at UTA. Other authors are former MIT postdoc Jaqueline Soares, currently an assistant professor at Federal University of Ouro Preto, Brazil, and Ramachandra Rao Dasari, associate director of the LBRC.

Silicon is commonly used to build “lab-on-a-chip” microfluidic devices, which can sort and analyze cells based on their molecular properties, as well as microelectronics devices. Such devices have many potential applications in research and diagnostics, but they could be even more useful if scientists could image the cells inside the devices, says Barman, who is now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins University.

To achieve that, Barman and colleagues took advantage of the fact that silicon is transparent to infrared and near-infrared wavelengths of light. They adapted a microscopy technique known as quantitative phase imaging, which works by sending a laser beam through a sample, then splitting the beam into two. By recombining those two beams and comparing the information carried by each one, the researchers can determine the sample’s height and its refractive index — a measure of how much the material forces light to bend as it passes through.

Traditional quantitative phase imaging uses a helium neon laser, which produces visible light, but for the new system the researchers used a titanium sapphire laser that can be tuned to infrared and near-infrared wavelengths. For this study, the researchers found that light with a wavelength of 980 nanometers worked best.

Using this system, the researchers measured changes in the height of red blood cells, with nanoscale sensitivity, through a silicon wafer similar to those used in most electronics labs.

As red blood cells flow through the body, they often have to squeeze through very narrow vessels. When these cells are infected with malaria, they lose this ability to deform, and form clogs in tiny vessels. The new microscopy technique could help scientists study how this happens, Dingari says; it could also be used to study the dynamics of the malformed blood cells that cause sickle cell anemia.

The researchers also used their new system to monitor human embryonic kidney cells as pure water was added to their environment — a shock that forces the cells to absorb water and swell up. The researchers were able to measure how much the cells distended and calculate the change in their index of refraction.

“Nobody has shown this kind of microscopy of cellular structures before through a silicon substrate,” Mohanty says.

“This is an exciting new direction that is likely to open up enormous opportunities for quantitative phase imaging,” says Gabriel Popescu, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who was not part of the research team.

“The possibilities are endless: From micro- and nanofluidic devices to structured substrates, the devices could target applications ranging from molecular sensing to whole-cell characterization and drug screening in cell populations,” Popescu says.

Mohanty’s lab at UTA is now using the system to study how neurons grown on a silicon wafer communicate with each other.

In the Scientific Reports paper, the researchers used silicon wafers that were about 150 to 200 microns thick, but they have since shown that thicker silicon can be used if the wavelength of light is increased into the infrared range. The researchers are also working on modifying the system so that it can image in three dimensions, similar to a CT scan.

The research was funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and Nanoscope Technologies, LLC.

Source: http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2013/seeing-through-silicon-1002.html

Scientists at MIT and the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) have developed a new type of microscopy that can image cells through a silicon wafer, allowing them to precisely measure the size and mechanical behavior of cells behind the wafer.

The new technology, which relies on near-infrared light, could help scientists learn more about diseased or infected cells as they flow through silicon microfluidic devices.

“This has the potential to merge research in cellular visualization with all the exciting things you can do on a silicon wafer,” says Ishan Barman, a former postdoc in MIT’s Laser Biomedical Research Center (LBRC) and one of the lead authors of a paper describing the technology in the Oct. 2 issue of the journal Scientific Reports.

Other lead authors of the paper are former MIT postdoc Narahara Chari Dingari and UTA graduate students Bipin Joshi and Nelson Cardenas. The senior author is Samarendra Mohanty, an assistant professor of physics at UTA. Other authors are former MIT postdoc Jaqueline Soares, currently an assistant professor at Federal University of Ouro Preto, Brazil, and Ramachandra Rao Dasari, associate director of the LBRC.

Silicon is commonly used to build “lab-on-a-chip” microfluidic devices, which can sort and analyze cells based on their molecular properties, as well as microelectronics devices. Such devices have many potential applications in research and diagnostics, but they could be even more useful if scientists could image the cells inside the devices, says Barman, who is now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins University.

To achieve that, Barman and colleagues took advantage of the fact that silicon is transparent to infrared and near-infrared wavelengths of light. They adapted a microscopy technique known as quantitative phase imaging, which works by sending a laser beam through a sample, then splitting the beam into two. By recombining those two beams and comparing the information carried by each one, the researchers can determine the sample’s height and its refractive index — a measure of how much the material forces light to bend as it passes through.

Traditional quantitative phase imaging uses a helium neon laser, which produces visible light, but for the new system the researchers used a titanium sapphire laser that can be tuned to infrared and near-infrared wavelengths. For this study, the researchers found that light with a wavelength of 980 nanometers worked best.

Using this system, the researchers measured changes in the height of red blood cells, with nanoscale sensitivity, through a silicon wafer similar to those used in most electronics labs.

As red blood cells flow through the body, they often have to squeeze through very narrow vessels. When these cells are infected with malaria, they lose this ability to deform, and form clogs in tiny vessels. The new microscopy technique could help scientists study how this happens, Dingari says; it could also be used to study the dynamics of the malformed blood cells that cause sickle cell anemia.

The researchers also used their new system to monitor human embryonic kidney cells as pure water was added to their environment — a shock that forces the cells to absorb water and swell up. The researchers were able to measure how much the cells distended and calculate the change in their index of refraction.

“Nobody has shown this kind of microscopy of cellular structures before through a silicon substrate,” Mohanty says.

“This is an exciting new direction that is likely to open up enormous opportunities for quantitative phase imaging,” says Gabriel Popescu, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who was not part of the research team.

“The possibilities are endless: From micro- and nanofluidic devices to structured substrates, the devices could target applications ranging from molecular sensing to whole-cell characterization and drug screening in cell populations,” Popescu says.

Mohanty’s lab at UTA is now using the system to study how neurons grown on a silicon wafer communicate with each other.

In the Scientific Reports paper, the researchers used silicon wafers that were about 150 to 200 microns thick, but they have since shown that thicker silicon can be used if the wavelength of light is increased into the infrared range. The researchers are also working on modifying the system so that it can image in three dimensions, similar to a CT scan.

The research was funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and Nanoscope Technologies, LLC.

Source: http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2013/seeing-through-silicon-1002.html

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)