Two University of California, Riverside assistant professors of physics are among a team of researchers that have developed a new way of seeing electrons cool off in an extremely short time period.

The development could have applications in numerous places where heat management is important, including visual displays, next-generation solar cells and photodetectors for optical communications.

In visual displays, such as those used in cell phones and computer monitors, and photodetectors, which have a wide variety of applications including solar energy harvesting and fiber optic telecommunications, much of the energy of the electrons is wasted by heating the material.

Controlling the flow of heat in the electrons, rather than wasting this energy by heating the material, could potentially increase the efficiency of such devices by converting excess energy into useful power.

The research is outlined in a paper, “Tuning ultrafast electron thermalization pathways in a van der Waals heterostructure,” published online Monday (Jan. 18) in the journal Nature Physics. Nathan Gabor and Joshua C.H. Lui, assistant professors of physics at UC Riverside, are among the co-authors.

In electronic materials, such as those used in semiconductors, electrons can be rapidly heated by pulses of light. The time it takes for electrons to cool each other off is extremely short, typically less than 1 trillionth of a second.

To understand this behavior, researchers use highly specialized tools that utilize ultra-fast laser techniques. In the two-dimensional material graphene cooling excited electrons occurs even faster, taking only 30 quadrillionths of a second. Previous studies struggled to capture this remarkably fast behavior.

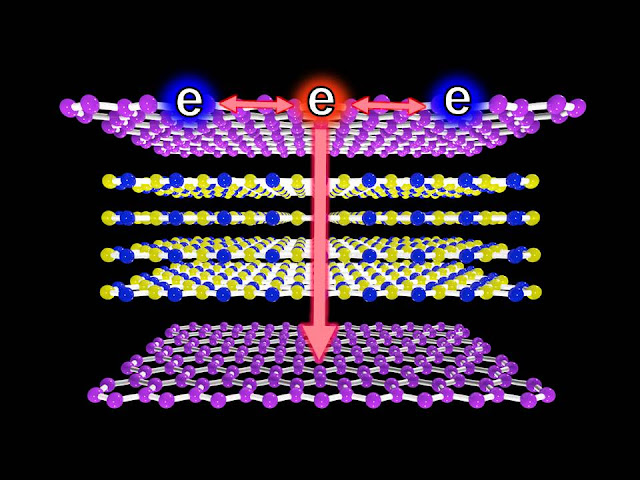

To solve that, the researchers used a completely different approach. They combined single layers of graphene with thin layers of insulating boron nitride to form a sandwich structure, known as a van der Waals heterostructure, which gives electrons two paths to choose from when cooling begins. Either the electrons stay in graphene and cool by bouncing off one another, or they get sucked out of graphene and move through the surrounding layer.

By tuning standard experimental knobs, such as voltage and optical pulse energy, the researchers found they can precisely control where the electrons travel and how long they take to cool off. The work provides new ways of seeing electrons cool off at extremely short time scales, and demonstrates novel devices for nanoscale optoelectronics.

This structure is one of the first in a new class of devices that are synthesized by mechanically stacking atomically thin membranes. By carefully choosing the materials that make up the device, the researchers developed a new type of optoelectronic photodetector that is only 10 nanometers thick. Such devices address the technological drive for ultra-dense, low-power, and ultra-efficient devices for integrated circuits.

The research follows advances made in 2011 Science article, in which the research team discovered the fundamental importance of hot electrons in the optoelectronic response of devices based on graphene.

Other co-authors of the Nature Physics paper are: Qiong Ma, Trond I. Andersen, Nityan L. Nair, Andrea F. Young, Wenjing Fang, Jing Kong, Nuh Gedik and Pablo Jarillo-Herrero, all of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Mathieu Massicotte and Frank H. L. Koppens, both of The Institute of Photonic Sciences in Spain; and Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi, both of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan.