One sheet, 15 centimetres in diameter and a few tenths of a millimetre thick can store as much as 1 F, which is similar to the supercapacitors currently on the market. The material can be recharged hundreds of times and each charge only takes a few seconds.

It’s a dream product in a world where the increased use of renewable energy requires new methods for energy storage – from summer to winter, from a windy day to a calm one, from a sunny day to one with heavy cloud cover.

”Thin films that function as capacitors have existed for some time. What we have done is to produce the material in three dimensions. We can produce thick sheets,” says Xavier Crispin, professor of organic electronics and co-author to the article just published in Advanced Science.

Other co-authors are researchers from KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Innventia, Technical University of Denmark and the University of Kentucky.

The material, power paper, looks and feels like a slightly plasticky paper and the researchers have amused themselves by using one piece to make an origami swan – which gives an indication of its strength.

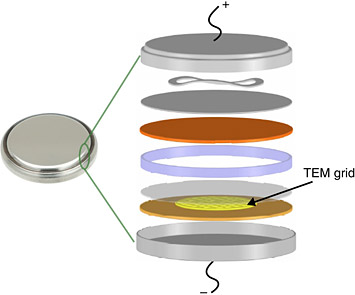

The structural foundation of the material is nanocellulose, which is cellulose fibres which, using high-pressure water, are broken down into fibres as thin as 20 nm in diameter. With the cellulose fibres in a solution of water, an electrically charged polymer (PEDOT:PSS), also in a water solution, is added. The polymer then forms a thin coating around the fibres.

”The covered fibres are in tangles, where the liquid in the spaces between them functions as an electrolyte,” explains Jesper Edberg, doctoral student, who conducted the experiments together with Abdellah Malti, who recently completed his doctorate.

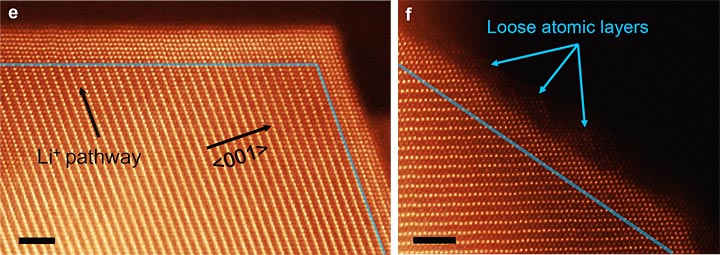

The new cellulose-polymer material has set a new world record in simultaneous conductivity for ions and electrons, which explains its exceptional capacity for energy storage. It also opens the door to continued development toward even higher capacity. Unlike the batteries and capacitors currently on the market, power paper is produced from simple materials – renewable cellulose and an easily available polymer. It is light in weight, it requires no dangerous chemicals or heavy metals and it is waterproof.

The Power Papers project has been financed by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation since 2012.

”They leave us to our research, without demanding lengthy reports, and they trust us. We have a lot of pressure on us to deliver, but it’s ok if it takes time, and we’re grateful for that,” says Professor Magnus Berggren, director of the Laboratory of Organic Electronics at Linköping University.

The new power paper is just like regular pulp, which has to be dehydrated when making paper. The challenge is to develop an industrial-scale process for this.

”Together with KTH, Acreo and Innventia we just received SEK 34 million from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research to continue our efforts to develop a rational production method, a paper machine for power paper,” says Professor Berggren.

Power paper – Four world records

Highest charge and capacitance in organic electronics, 1 C and 2 F (Coulomb and Farad).

Highest measured current in an organic conductor, 1 A (Ampere).

Highest capacity to simultaneously conduct ions and electrons.

Highest transconductance in a transistor, 1 S (Siemens)

Publication:

An Organic Mixed Ion-Electron Conductor for Power Electronics, Abdellah Malti, Jesper Edberg, Hjalmar Granberg, Zia Ullah Khan, Jens W Andreasen, Xianjie Liu, Dan Zhao, Hao Zhang, Yulong Yao, Joseph W Brill, Isak Engquist, Mats Fahlman, Lars Wågberg, Xavier Crispin and Magnus Berggren. Advanced Science, DOI 10.1002/advs.201500305