The first direct measurement of resistance to bending in a nanoscale membrane has been made by scientists from the University of Chicago, Peking University, the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory.

Their research provides researchers with a new, simpler method to measure nanomaterials' resistance to bending and stretching, and opens new possibilities for creating nano-sized objects and machines by controlling and tailoring that resistance. (A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter, about as long as your fingernails grow in one second.)

The research team worked with a gold nanomembrane. "It's like a sheet of paper, only ten thousand times thinner," said Heinrich Jaeger of the University of Chicago. "If you slide a piece of paper over the edge of a table, it bends down. The gold nanomembrane behaves the same way, but it's a hundred times stiffer than the paper if scaled to the same thickness — a hundred times more resistant to bending.

"Researchers around the world are seeking ways to manipulate ultrathin nanomaterials into stable three-dimensional objects," Jaeger said. "The challenge is how to make a two-dimensional film into a three-dimensional shape when the film is so thin and flexible. It's like nano-origami: how do you get it to hold a stable shape? You need something stiffer than you would expect. It turns out that many nanomembranes may already possess that property."

"We were surprised to find that the gold nanomembrane was over a hundred times more resistant to bending than we predicted, based on standard elasticity theory and our experience with thin sheets, such as paper," said Xiao-Min Lin, who fabricated the gold nanoparticles in specialized facilities at the Center for Nanoscale Materials, a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Argonne. "We believe it's related to membrane's internal structure. The membrane is only one nanoparticle thick, so it's essentially all surface with very little interior volume. Minor structural disorder along its surface would significantly increase its resistant to bending. We also think molecular packing between nanoparticles might strongly affect its ability to bend."

Critical to the team's discovery were a new method for creating gold membranes that roll themselves into nano-sized scrolls and a new technique for measuring the scroll's resistance to bending. Both were developed by Yifan Wang of the University of Chicago using CNM's facilities.

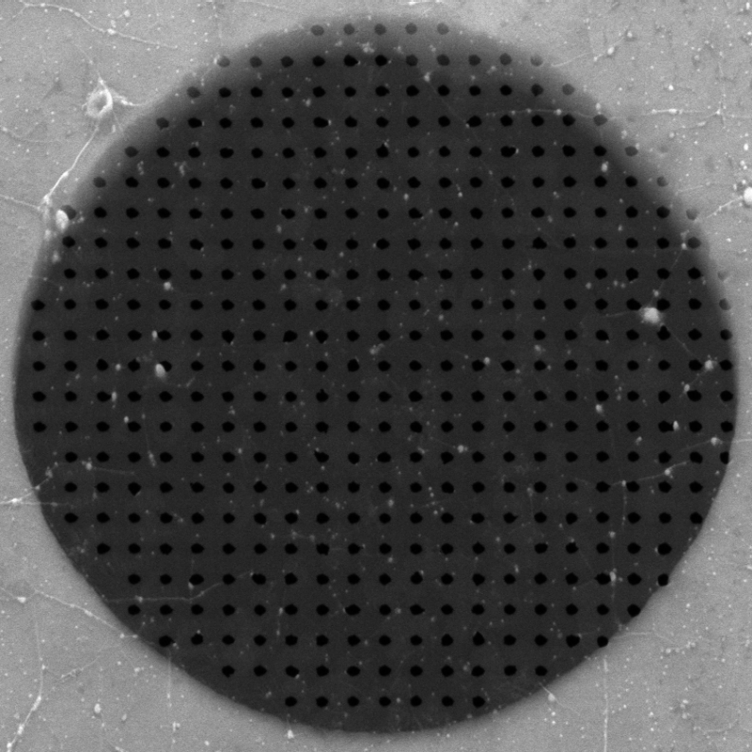

The gold nanoscrolls were self-assembled by suspending a fluid containing gold nanoparticles on a carbon screen. As the fluid dried, it left a gold membrane suspended like a nano-drumhead across the screen's circular holes. As the membranes continued to dry and tighten, one edge pulled loose from the screen, and the membrane spontaneously rolled up to form a hollow tube.

"There are many ways to make nanoparticle tubes," said Wang, "but they involve things like exposing membranes to electron beams, which can alter physical properties, such as their resistance to bending and stretching – the very things we wanted to measure. We needed a non-invasive way to make nanoparticle tubes without changing those properties."

The team found that a nanomembrane's resistance to both bending and stretching can be calculated from a single experiment that uses atomic force microscopy to measure bending resistance along the length of a monolayer membrane that has been rolled into a hollow cylinder.

(Atomic force microscopy uses a physical probe to measure surface details as small as a fraction of a nanometer.) Previous methods required two separate experiments on nanoscale membranes — one to measure stretching resistance and another to measure bending resistance.

"The tube's response to small local indentations is a signature of contributions to both bending and stretching," said Wang. "As a result, a single set of measurements of the resistance to indentation along the length of the tube provides direct access to its bending modulus and stretching modulus — key parameters needed to calculate resistance to both bending and stretching."

Since the measurement is based only on elasticity theory and the tube's geometry, Wang explained, it should have general applicability across a wide range of materials and size scales, from nano- and microtubules to truly macroscopic objects.

"Ultrathin sheets just one nanoparticle thick have unique mechanical properties," Wang said. "This experiment provides new input for independent control of resistance to bending and stretching at the nanoscale. It should be possible to tailor bending and stretching parameters and to develop new nanomaterials and nano-objects with specific desirable properties."

The paper, "Strong Resistance to Bending Observed for Nanoparticle Membranes," was published in the online journal NanoLetters.

Other members of the research team were Jianhui Liao of Peking University in China, who visited Jaeger's lab at the University of Chicago for an extended research stay and performed the first experiments and measurements on the tubes; postdoc Sean McBride of the University of Chicago; and theory postdoc Efi Efrati of the University of Chicago, who helped with the modeling and who is now on the faculty at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the University of Chicago's Materials Research Science and Engineering Center. The Center for Nanoscale Materials is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.