A team of neurosurgeons and engineers has developed wireless brain sensors that monitor intracranial pressure and temperature and then are absorbed by the body, negating the need for surgery to remove the devices.

Such implants, developed by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and engineers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, potentially could be used to monitor patients with traumatic brain injuries, but the researchers believe they can build similar absorbable sensors to monitor activity in organ systems throughout the body. Their findings are published online Jan. 18 in the journal Nature.

"Electronic devices and their biomedical applications are advancing rapidly," said co-first author Rory K. J. Murphy, MD, a neurosurgery resident at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. "But a major hurdle has been that implants placed in the body often trigger an immune response, which can be problematic for patients. The benefit of these new devices is that they dissolve over time, so you don't have something in the body for a long time period, increasing the risk of infection, chronic inflammation and even erosion through the skin or the organ in which it's placed. Plus, using resorbable devices negates the need for surgery to retrieve them, which further lessens the risk of infection and further complications."

Murphy is most interested in monitoring pressure and temperature in the brains of patients with traumatic brain injury.

About 50,000 people die of such injuries annually in the United States. When patients with such injuries arrive in the hospital, doctors must be able to accurately measure intracranial pressure in the brain and inside the skull because an increase in pressure can lead to further brain injury, and there is no way to reliably estimate pressure levels from brain scans or clinical features in patients.

"However, the devices commonly used today are based on technology from the 1980s," Murphy explained. "They're large, they're unwieldy, and they have wires that connect to monitors in the intensive care unit. They give accurate readings, and they help, but there are ways to make them better."

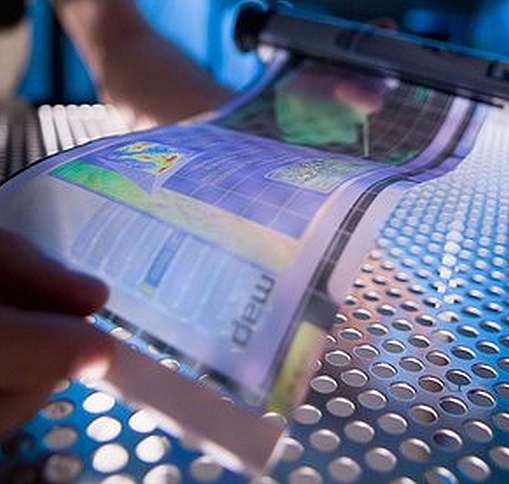

Murphy collaborated with engineers in the laboratory of John A. Rogers, PhD, a professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Illinois, to build new sensors. The devices are made mainly of polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) and silicone, and they can transmit accurate pressure and temperature readings, as well as other information.

"With advanced materials and device designs, we demonstrated that it is possible to create electronic implants that offer high performance and clinically relevant operation in hardware that completely resorbs into the body after the relevant functions are no longer needed," Rogers said. "This type of bio-electric medicine has great potential in many areas of clinical care."

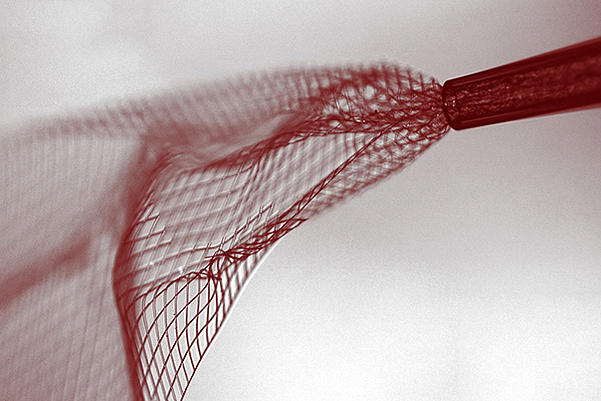

The researchers tested the sensors in baths of saline solution that caused them to dissolve after a few days. Next, they tested the devices in the brains of laboratory rats.

Having shown that the sensors are accurate and that they dissolve in the solution and in the brains of rats, the researchers now are planning to test the technology in patients.

"In terms of the major challenges involving size and scale, we've already crossed some key bridges," said co-senior author Wilson Z. Ray, MD, assistant professor of neurological and orthopaedic surgery at Washington University.

In patients with traumatic brain injuries, neurosurgeons attempt to decrease the pressure inside the skull using medications. If pressure cannot be reduced sufficiently, patients often undergo surgery. The new devices could be placed into the brain at multiple locations during such operations.

"The ultimate strategy is to have a device that you can place in the brain -- or in other organs in the body -- that is entirely implanted, intimately connected with the organ you want to monitor and can transmit signals wirelessly to provide information on the health of that organ, allowing doctors to intervene if necessary to prevent bigger problems," Murphy said. "And then after the critical period that you actually want to monitor, it will dissolve away and disappear."