Key sign of quark-gluon plasma (QGP) and evidence for a long-debated quantum phenomenon

Scientists in the STAR collaboration at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a particle accelerator exploring nuclear physics and the building blocks of matter at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, have new evidence for what’s called a “chiral magnetic wave” rippling through the soup of quark-gluon plasma created in RHIC’s energetic particle smashups.

The presence of this wave is one of the consequences scientists were expecting to observe in the quark-gluon plasma—a state of matter that existed in the early universe when quarks and gluons, the building blocks of protons and neutrons, were free before becoming inextricably bound within those larger particles. The tentative discovery, if confirmed, would provide additional evidence that RHIC’s collisions of energetic gold ions recreate nucleus-size blobs of the fiery plasma thousands of times each second. It would also provide circumstantial evidence in support of a separate, long-debated quantum phenomenon required for the wave’s existence. The findings are described in a paper that will be highlighted as an Editors' Suggestion in Physical Review Letters.

To try to understand these results, let’s take a look deep within the plasma to a seemingly surreal world where magnetic fields separate left- and right-“handed” particles, setting up waves that have differing effects on how negatively and positively charged particles flow.

The presence of this wave is one of the consequences scientists were expecting to observe in the quark-gluon plasma. It also provides circumstantial evidence for a separate, long-debated quantum phenomenon.

“What we measure in our detector is the tendency of negatively charged particles to come out of the collisions around the ‘equator’ of the fireball, while positively charged particles are pushed to the poles,” said STAR collaborator Hongwei Ke, a postdoctoral fellow at Brookhaven. But the reasons for this differential flow, he explained, begin when the gold ions collide.

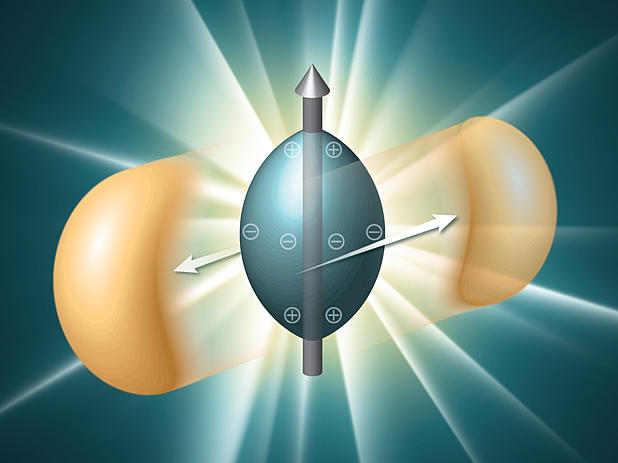

The ions are gold atoms stripped of their electrons, leaving 79 positively charged protons in a naked nucleus. When these ions smash into one another even slightly off center, the whole mix of charged matter starts to swirl. That swirling positive charge sets up a powerful magnetic field perpendicular to the circulating mass of matter, Ke explained. Picture a spinning sphere with north and south poles.

Within that swirling mass, there are huge numbers of subatomic particles, including quarks and gluons at the early stage, and other particles at a later stage, created by the energy deposited in the collision zone. Many of those particles also spin as they move through the magnetic field. The direction of their spin relative to their direction of motion is a property called chirality, or handedness; a particle moving away from you spinning clockwise would be right-handed, while one spinning counterclockwise would be left-handed.

The STAR detector at RHIC tracks particles emerging from thousands of subatomic smashups per second.

According to Gang Wang, a STAR collaborator from the University of California at Los Angeles, if the numbers of particles and antiparticles are different, the magnetic field will affect these left- and right-handed particles differently, causing them to separate along the axis of the magnetic field according to their “chiral charge.”

“This ‘chiral separation’ acts like a seed that, in turn, causes particles with different charges to separate,” Gang said. “That triggers even more chiral separation, and more charge separation, and so on—with the two effects building on one another like a wave, hence the name ‘chiral magnetic wave.’ In the end, what you see is that these two effects together will push more negative particles into the equator and the positive particles to the poles.”

To look for this effect, the STAR scientists measured the collective motion of certain positively and negatively charged particles produced in RHIC collisions. They found that the collective elliptic flow of the negatively charged particles—their tendency to flow out along the equator—was enhanced, while the elliptic flow of the positive particles was suppressed, resulting in a higher abundance of positive particles at the poles. Importantly, the difference in elliptic flow between positive and negative particles increased with the net charge density produced in RHIC collisions.

According to the STAR publication, this is exactly what is expected from calculations using the theory predicting the existence of the chiral magnetic wave. The authors note that the results hold out for all energies at which a quark-gluon plasma is believed to be created at RHIC, and that, so far, no other model can explain them.

The finding, says Aihong Tang, a STAR physicist from Brookhaven Lab, has a few important implications.

“First, seeing evidence for the chiral magnetic wave means the elements required to create the wave must also exist in the quark-gluon plasma. One of these is the chiral magnetic effect—the quantum physics phenomenon that causes the electric charge separation along the axis of the magnetic field—which has been a hotly debated topic in physics. Evidence of the wave is evidence that the chiral magnetic effect also exists.” Tang said.

The chiral magnetic effect is also related to another intriguing observation at RHIC of more-localized charge separation within the quark-gluon plasma. So this new evidence of the wave provides circumstantial support for those earlier findings.

Finally, Tang pointed out that the process resulting in propagation of the chiral magnetic wave requires that “chiral symmetry”—the independent identities of left- and right-handed particles—be “restored.”

“In the ‘ground state’ of quantum chromodynamics (QCD)—the theory that describes the fundamental interactions of quarks and gluons—chiral symmetry is broken, and left- and right-handed particles can transform into one another. So the chiral charge would be eliminated and you wouldn’t see the propagation of the chiral magnetic wave,” said nuclear theorist Dmitri Kharzeev, a physicist at Brookhaven and Stony Brook University. But QCD predicts that when quarks and gluons are deconfined, or set free from protons and neutrons as in a quark-gluon plasma, chiral symmetry is restored. So the observation of the chiral wave provides evidence for chiral symmetry restoration—a key signature that quark-gluon plasma has been created.

“How does deconfinement restore the symmetry? This is one of the main things we want to solve,” Kharzeev said. “We know from the numerical studies of QCD that deconfinement and restoration happen together, which suggests there is some deep relationship. We really want to understand that connection.”

Brookhaven physicist Zhangbu Xu, spokesperson for the STAR collaboration, added, “To improve our ability to search for and understand the chiral effects, we’d like to compare collisions of nuclei that have the same mass number but different numbers of protons—and therefore, different amounts of positive charge (for example, Ruthenium, mass number 96 with 44 protons, and Zirconium, mass number 96 with 40 protons). That would allow us to vary the strength of the initial magnetic field while keeping all other conditions essentially the same.”

Research at RHIC, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, is supported by the Office of Science (NP) and these agencies and organizations.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Source: http://www.nanotechnologyworld.org/#!Scientists-See-Ripples-of-a-ParticleSeparating-Wave-In-Primordial-Plasma/c89r/557596ec0cf2e4994fb7bcef