absolute zero. This required building a sensor capable of resolving the smallest vibration allowed by quantum mechanics.

Quantum mechanics predicts that a mechanical object, even when cooled to absolute zero, produces small vibrations, called “zero-point fluctuations”. The reason we don’t observe these vibrations in everyday life is that for a tangibly sized object at room temperature, they are much smaller than the vibrations caused by thermal motion of atoms. EPFL researchers have overcome this challenge by coupling a micrometer-sized glass string to a very precise, optical displacement sensor. The sensor is so precise that it can, in principle, resolve the string’s zero-point fluctuations before they are obscured by thermal vibrations. Combining this low-noise readout with a feedback force, the scientists were able to suppress the string’s thermal vibrations to a magnitude only 10 times larger than their zero-point value – in effect realizing an extreme version of a noise cancellation headphone. The work is published in Nature.

Feedback at the quantum limit

Feedback is a ubiquitous tool in modern engineering, used in applications ranging from cruise control to atomic clocks. The basic paradigm uses a sensor to monitor the state of a system (e.g. a car's velocity) and an actuator (e.g. an engine throttle) to steer the system along a desired path (e.g. within the ed limit).

As sensor technology advances, it has been proposed to use such "feedback control" to prepare and stabilize delicate quantum states – for instance, the celebrated half-living, half-dead state of Schrodinger's Cat. Aside from their fundamental interest, the ability to cultivate quantum states is expected to play a crucial role in future technologies such as quantum computers.

The main challenge to quantum feedback control is something called "decoherence", which dictates that the behavior of a system in a quantum state is rapidly destroyed by its interaction with the thermal environment. This places stringent requirements on the speed and precision of the sensor. Successful demonstrations have therefore been limited to a small subset of well-isolated systems, like individual trapped atoms, photons, and superconducting circuits.

Shedding light on the problem

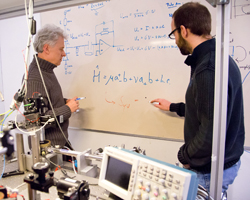

The lab of Tobias J. Kippenberg at EPFL has fabricated an extremely precise optical position sensor that may – surprisingly – extend quantum feedback control to engineered mechanical devices . In the "blink of an eye" (0.3 - 0.4 seconds) the sensor is capable of resolving a displacement 100 times smaller than the size of a proton. Making use of such a high-speed sensor, it is possible to capture an image in which the blur (or uncertainty) of an object's position is smaller than the uncertainty caused by the thermal motion of its constituent atoms.

Using a continuous stream of such "freeze frames", the researchers have used feedback to reduce the motion of a mechanical device – in this case the vibration of a micron-sized, glass string – to the value it would have if the device were cooled 0.001 degrees above absolute zero. The residual vibration of the string is only 10 times bigger than the minimum (``zero-point”) value allowed by quantum mechanics. This means that the string spends 10% of its time in its quantum “ground state.”

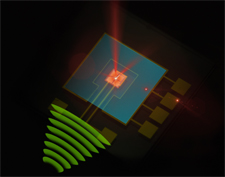

Kippenberg’s lab specializes in the field of “cavity optomechanics”. In optomechanics, much like in high-speed photography, the motion of a mechanical device is imaged using an intense beam of light. The challenge in this case was to focus the light into a very small spot, in order to maximize its interaction with the tiny string.

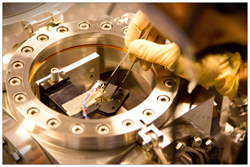

The researchers achieved this by confining the light and the string to a miniature “hall of mirrors” called an “optical microcavity”. Developed in the Center of MicroTechnology at EPFL, the optical microcavity is a small, disk-shaped piece of glass, above which the string is suspended by 50 nm. Laser light coupled into the disk circulates along its periphery ~10,000 times, each time reflecting off the string and incurring a small delay in proportion to the string’s vibration amplitude. This delay is measured using a technique called interferometry.

To cool the string’s vibration, the researchers took advantage of a well-known side-effect of optical measurement: namely, that each reflection of the circulating field also imparts a small force, called “radiation pressure”, on the string. Using a sequence of electronics, the researchers imprinted a measurement of the string’s vibration onto the intensity of a second laser field. As lead author Dal Wilson explains, “The radiation pressure applied by the second field, when appropriately delayed, exactly opposes the thermal motion of the string, like a noise-cancellation headphone”.

http://www.nanotechnologyworld.org/#!Measuring-the-smallest-vibration/c89r/55c8cde20cf2244af607fa2e