Gold nanoparticles have unusual optical, electronic and chemical properties, which scientists are seeking to put to use in a range of new technologies, from nanoelectronics to cancer treatments.

Some of the most interesting properties of nanoparticles emerge when they are brought close together – either in clusters of just a few particles or in crystals made up of millions of them. Yet particles that are just millionths of an inch in size are too small to be manipulated by conventional lab tools, so a major challenge has been finding ways to assemble these bits of gold while controlling the three-dimensional shape of their arrangement.

One approach that researchers have developed has been to use tiny structures made from synthetic strands of DNA to help organize nanoparticles. Since DNA strands are programmed to pair with other strands in certain patterns, scientists have attached individual strands of DNA to gold particle surfaces to create a variety of assemblies. But these hybrid gold-DNA nanostructures are intricate and expensive to generate, limiting their potential for use in practical materials. The process is similar, in a sense, to producing books by hand.

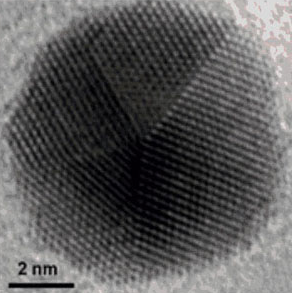

Enter the nanoparticle equivalent of the printing press. It’s efficient, re-usable and carries more information than previously possible. In results reported online in Nature Chemistry, researchers from McGill’s Department of Chemistry outline a procedure for making a DNA structure with a specific pattern of strands coming out of it; at the end of each strand is a chemical “sticky patch.” When a gold nanoparticle is brought into contact to the DNA nanostructure, it sticks to the patches. The scientists then dissolve the assembly in distilled water, separating the DNA nanostructure into its component strands and leaving behind the DNA imprint on the gold nanoparticle. (See illustration.)

“These encoded gold nanoparticles are unprecedented in their information content,” says senior author Hanadi Sleiman, who holds the Canada Research Chair in DNA Nanoscience. “The DNA nanostructures, for their part, can be re-used, much like stamps in an old printing press.”

From stained glass to optoelectronics

Some of the properties of gold nanoparticles have been recognized for centuries. Medieval artisans added gold chloride to molten glass to create the ruby-red colour in stained-glass windows – the result, as chemists figured out much later, of the light-scattering properties of tiny gold particles.

Now, the McGill researchers hope their new production technique will help pave the way for use of DNA-encoded nanoparticles in a range of cutting-edge technologies. First author Thomas Edwardson says the next step for the lab will be to investigate the properties of structures made from these new building blocks. “In much the same way that atoms combine to form complex molecules, patterned DNA gold particles can connect to neighbouring particles to form well-defined nanoparticle assemblies.”

These could be put to use in areas including optoelectronic nanodevices and biomedical sciences, the researchers say. The patterns of DNA strands could, for example, be engineered to target specific proteins on cancer cells, and thus serve to detect cancer or to selectively destroy cancer cells.

Financial support for the research was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Centre for Self-Assembled Chemical Structures, the Canada Research Chairs Program and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“Transfer of molecular recognition information from DNA nanostructures to gold nanoparticles,” Thomas G. W. Edwardson et al, Nature Chemistry, Jan. 4, 2016. DOI: 10.1038/nchem.2420

http://www.nature.com/nchem/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nchem.2420.html

http://www.nature.com/nchem/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nchem.2420.html