Finding could have implications for high-temperature superconductivity

A team of physicists led by Caltech's David Hsieh has discovered an unusual form of matter—not a conventional metal, insulator, or magnet, for example, but something entirely different. This phase, characterized by an unusual ordering of electrons, offers possibilities for new electronic device functionalities and could hold the solution to a long-standing mystery in condensed matter physics having to do with high-temperature superconductivity—the ability for some materials to conduct electricity without resistance, even at "high" temperatures approaching –100 degrees Celsius.

"The discovery of this phase was completely unexpected and not based on any prior theoretical prediction," says Hsieh, an assistant professor of physics, who previously was on a team that discovered another form of matter called a topological insulator. "The whole field of electronic materials is driven by the discovery of new phases, which provide the playgrounds in which to search for new macroscopic physical properties."

Hsieh and his colleagues describe their findings in the November issue of Nature Physics, and the paper is now available online. Liuyan Zhao, a postdoctoral scholar in Hsieh's group, is lead author on the paper.

The physicists made the discovery while testing a laser-based measurement technique that they recently developed to look for what is called multipolar order. To understand multipolar order, first consider a crystal with electrons moving around throughout its interior. Under certain conditions, it can be energetically favorable for these electrical charges to pile up in a regular, repeating fashion inside the crystal, forming what is called a charge-ordered phase. The building block of this type of order, namely charge, is simply a scalar quantity—that is, it can be described by just a numerical value, or magnitude.

In addition to charge, electrons also have a degree of freedom known as spin. When spins line up parallel to each other (in a crystal, for example), they form a ferromagnet—the type of magnet you might use on your refrigerator and that is used in the strip on your credit card. Because spin has both a magnitude and a direction, a spin-ordered phase is described by a vector.

Over the last several decades, physicists have developed sophisticated techniques to look for both of these types of phases. But what if the electrons in a material are not ordered in one of those ways? In other words, what if the order were described not by a scalar or vector but by something with more dimensionality, like a matrix? This could happen, for example, if the building block of the ordered phase was a pair of oppositely pointing spins—one pointing north and one pointing south—described by what is known as a magnetic quadrupole. Such examples of multipolar-ordered phases of matter are difficult to detect using traditional experimental probes.

As it turns out, the new phase that the Hsieh group identified is precisely this type of multipolar order.

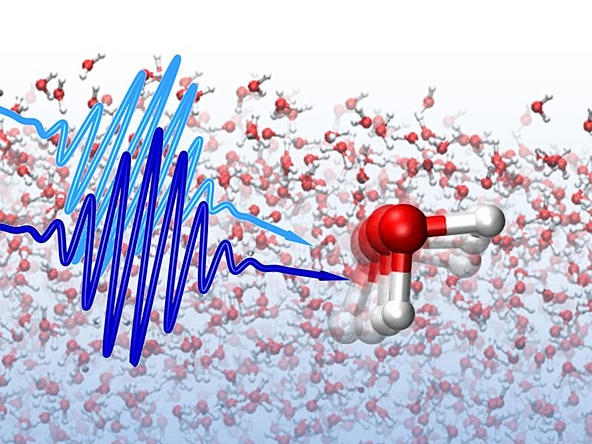

To detect multipolar order, Hsieh's group utilized an effect called optical harmonic generation, which is exhibited by all solids but is usually extremely weak. Typically, when you look at an object illuminated by a single frequency of light, all of the light that you see reflected from the object is at that frequency. When you shine a red laser pointer at a wall, for example, your eye detects red light. However, for all materials, there is a tiny amount of light bouncing off at integer multiples of the incoming frequency. So with the red laser pointer, there will also be some blue light bouncing off of the wall. You just do not see it because it is such a small percentage of the total light. These multiples are called optical harmonics.

The Hsieh group's experiment exploited the fact that changes in the symmetry of a crystal will affect the strength of each harmonic differently. Since the emergence of multipolar ordering changes the symmetry of the crystal in a very specific way—a way that can be largely invisible to conventional probes—their idea was that the optical harmonic response of a crystal could serve as a fingerprint of multipolar order.

"We found that light reflected at the second harmonic frequency revealed a set of symmetries completely different from those of the known crystal structure, whereas this effect was completely absent for light reflected at the fundamental frequency," says Hsieh. "This is a very clear fingerprint of a specific type of multipolar order."

The specific compound that the researchers studied was strontium-iridium oxide (Sr2IrO4), a member of the class of synthetic compounds broadly known as iridates. Over the past few years, there has been a lot of interest in Sr2IrO4 owing to certain features it shares with copper-oxide-based compounds, or cuprates. Cuprates are the only family of materials known to exhibit superconductivity at high temperatures—exceeding 100 Kelvin (–173 degrees Celsius).

Structurally, iridates and cuprates are very similar. And like the cuprates, iridates are electrically insulating antiferromagnets that become increasingly metallic as electrons are added to or removed from them through a process called chemical doping. A high enough level of doping will transform cuprates into high-temperature superconductors, and as cuprates evolve from being insulators to superconductors, they first transition through a mysterious phase known as the pseudogap, where an additional amount of energy is required to strip electrons out of the material.

For decades, scientists have debated the origin of the pseudogap and its relationship to superconductivity—whether it is a necessary precursor to superconductivity or a competing phase with a distinct set of symmetry properties. If that relationship were better understood, scientists believe, it might be possible to develop materials that superconduct at temperatures approaching room temperature.

Recently, a pseudogap phase also has been observed in Sr2IrO4—and Hsieh's group has found that the multipolar order they have identified exists over a doping and temperature window where the pseudogap is present. The researchers are still investigating whether the two overlap exactly, but Hsieh says the work suggests a connection between multipolar order and pseudogap phenomena.

"There is also very recent work by other groups showing signatures of superconductivity in Sr2IrO4 of the same variety as that found in cuprates," he says. "Given the highly similar phenomenology of the iridates and cuprates, perhaps iridates will help us resolve some of the longstanding debates about the relationship between the pseudogap and high-temperature superconductivity."

Hsieh says the finding emphasizes the importance of developing new tools to try to uncover new phenomena. "This was really enabled by a simultaneous technique advancement," he says.

Furthermore, he adds, these multipolar orders might exist in many more materials. "Sr2IrO4 is the first thing we looked at, so these orders could very well be lurking in other materials as well, and that's exactly what we are pursuing next."

Additional Caltech authors on the paper, "Evidence of an odd-parity hidden order in a spin–orbit coupled correlated iridate," are Darius H. Torchinsky, Hao Chu, and Vsevolod Ivanov. Ron Lifshitz of Tel Aviv University, Rebecca Flint of Iowa State University, and Tongfei Qi and Gang Cao of the University of Kentucky are also coauthors. The work was supported by funding from the Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter, an NSF Physics Frontiers Center with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.